‘They’re helping me save the rest of my life’: Rutland organization helps incarcerated people find sobriety

| Published: 05-28-2023 6:42 PM |

RUTLAND — In 2018, Mike St. Pierre was a year into his most recent incarceration at Rutland’s Marble Valley Regional Correctional Facility when he felt drawn to attend a presentation by the local substance use recovery center. After listening to the visiting peer counselors talk about their paths to recovery, he decided to sign up for their prison programs.

“Maybe this is something I need, and I won’t keep going back to jail,” St. Pierre, 58, recalls thinking at the time.

Through these group meetings and one-on-one recovery coaching with the Turning Point Center of Rutland, St. Pierre finally acknowledged he had a drinking problem, which — coupled with misuse of anxiety medication — had contributed to his committing numerous crimes since his teens.

In his latest conviction, for burglarizing a neighbor in 2017, St. Pierre admitted he broke into the Chittenden home to steal alcohol. He was sentenced to five to 15 years in prison.

“It’s been a nightmare. I destroyed my life,” he told VTDigger during a series of interviews. The Rutland city resident has spent almost half of his life incarcerated, and some family members had severed ties with him.

But with the help of the recovery center’s personnel, St. Pierre said he has been able to turn his life around. “I owe it to them,” he said.

The Turning Point Center of Rutland offers the only community-based recovery coaching program within Vermont’s corrections system — a service that several formerly incarcerated people told VTDigger has helped them find sobriety and rebuild their lives.

The center traces its volunteer work at Marble Valley to recovery group meetings in 2016, an offshoot of a short-term grant program related to Vermont’s medication-assisted treatment system. In 2018, responding to requests from incarcerated individuals, the nonprofit organization added individualized recovery coaching.

Article continues after...

Yesterday's Most Read Articles

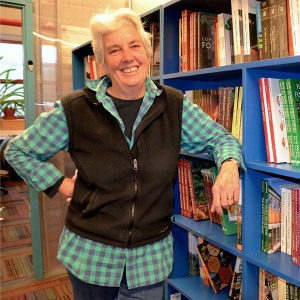

At the programs’ peak, before Vermont correctional facilities went into lockdown in March 2020 because of the COVID-19 pandemic, the recovery center was serving around 45 people at Marble Valley, said center director Tracy Hauck.

Because a significant number of incarcerated people have a substance use disorder, Hauck said offering recovery programs in correctional facilities is a golden opportunity to connect with them.

“You can’t just put people in time-out, in jail, and expect them to sit and think,” said Hauck, who spearheaded her center’s outreach at Marble Valley. “That’s the time when they need to have resources, so that if they’re open to it, they can change things.”

Vermont has a unified jail and prison system, where facilities hold both people who are detained before trial and those serving sentences. The state’s six correctional facilities altogether house about 1,200 people on any given day, according to the state Department of Corrections. Marble Valley has capacity for 135 residents.

John Cassarino, Marble Valley’s volunteer services coordinator of nearly 30 years, underscored the value of Rutland Turning Point’s recovery coaching program. For one, he said, the coaches are themselves people in recovery and can empathize with participants. Another advantage is that participants receive individualized, private mentoring.

“It shows the resident population that there are people who have had similar struggles and who have overcome them and are working hard continuing to give back,” he said.

To date, about 200 Marble Valley residents have received in-person recovery coaching, said Cassarino, whom the Rutland Turning Point credits with helping open the correctional facility’s doors to volunteers from the center.

Cassarino said he has seen how the center’s prison programs have provided participants with a guiding hand in re-entering society.

Once released, they can continue receiving coaching and attending group meetings, whether in the Rutland area or elsewhere. Rutland Turning Point can also link them with social services, such as transitional housing, job search assistance and food pantries. Most of all, the center wants to be a welcoming place, given that isolation can be dangerous for people in recovery.

A statewide data analysis by the Vermont Department of Health found that, amid social distancing during the pandemic, 60% of people who fatally overdosed from drugs and alcohol did so at home. And 52% were on their own when they died.

Although sobriety is the ideal goal, Hauck said, what’s more important is that people in recovery feel safe and accepted.

“Wherever they’re at in their recovery process, whether they’ve had a slip or they’re struggling,” she said, “we want them to feel like they can come in and talk openly about it to get back on track.”

Rutland Turning Point’s general budget usually pays for the cost of its prison outreach: staff wages and program materials. From 2018 to 2020, the work was funded by a grant from the Rutland Regional Medical Center. In other years, Hauck said, some short-term grants have helped keep it going.

She said not being funded by the Vermont Department of Corrections establishes the center as an independent entity, helping Turning Point personnel gain the trust and confidence of incarcerated people.

When prison visits were suspended during the pandemic lockdown, Lewis Nielson, a 73-year-old volunteer recovery coach at the center, was concerned program participants would feel abandoned and lose any gains they’d made.

He suggested staying in touch with them in writing. That meant sending letters back and forth through the postal service, since the corrections department doesn’t allow facility volunteers to communicate with incarcerated people by phone or email for security reasons. Turning Point didn’t resume in-person meetings at Marble Valley until August 2022.

During the intervening 2½ years, Nielson, a Castleton resident and retired music composer, regularly corresponded with about 40 incarcerated people. Their letters also kept arriving at the recovery center.

At the Turning Point Center in downtown Rutland one morning in March, Hauck held out a stack of mail that was sent by incarcerated individuals during the pandemic. “That’s not even all of them,” she said, adding there were hundreds more stored in an office filing cabinet.

Until the Rutland Turning Point replaces a recently retired employee who ran the group meetings at Marble Valley, it’s just Nielson visiting the facility two days a week to hold coaching sessions. He also pays for his gas mileage out of pocket.

He won’t take any credit for the progress of his Marble Valley clients, despite the thousands of unpaid hours he has spent meeting with them, writing to them and talking to them on the phone once they’re released. Those who’ve been successful in their recovery, he said, had merely been ready to listen and make important changes in their lives.

As a person who is himself in recovery from drinking, Nielson said the time he spends with people who are incarcerated or formerly incarcerated has benefited him too. “I’m doing this to stay sober myself,” he said. “They helped me as much as I’d ever helped them.”

But people who have been mentored by Nielson say he’s been invaluable.

Among those who consistently wrote to him during the lockdown was M.J., who’d spent two years at Marble Valley. If it weren’t for the recovery center’s intervention, the 39-year-old Rutland County resident said he might be dead by now.

“I was getting suicidal,” said M.J., who spoke on condition that only his initials be used, citing concerns of retaliation for speaking to the media.

Because of his traumatic childhood and difficult experiences as an adult, M.J. said he’d contemplated suicide numerous times. Before landing at Marble Valley, his goal had been “to drink my brain dead.”

In early 2019, he was booked at the Rutland correctional facility on an assault charge. M.J. said he largely stayed in his cell, where his suicidal ideations continued. He eventually realized that, to stay alive and out of trouble, he needed to remain sober. He began attending Turning Point group meetings and recovery coaching.

“Even if they couldn’t give any advice or anything of that nature, at least somebody would be there to hear my voice,” M.J. said over coffee after work one afternoon. “It helped for more than just drinking issues.”

He also wanted to surround himself with people who could be a positive influence. He said the recovery center’s programs were among the few things of value he found in the correctional facility.

“Those places are not designed to rehabilitate you,” he said. “The only rehabilitation that goes on in that place comes from an outside source, like Turning Point.”

He was released from Marble Valley under probationary conditions in 2021. He has since found employment with a subcontractor and saved enough money to buy a secondhand truck. Though his work keeps his schedule full, once a week after work, he still meets with Nielson for recovery coaching.

M.J. has now been sober for four years. He has also kept all the letters Nielson sent him at Marble Valley, along with several drawings on makeshift drafting paper that he made to occupy his time. He described the hours he spent creating one sheet of drafting paper, making vertical and horizontal lines that were 1/8-inch apart, which now costs him about 50 cents apiece from a store.

Through Turning Point, M.J. said, he has found not only practical help and moral support but also learned about accountability. “I’m doing better now since I’ve had them in my life,” he said. He said his thoughts of suicide have also subsided.

At age 56, Peter had been taken to Marble Valley in 2019 on a charge of driving under the influence of alcohol. It was the latest in a string of DUI offenses since he became an adult, on top of sexual assault, and lewd and lascivious conduct, in his younger years.

He’d been in and out of prison since his 20s. “Everything I’ve done wrong was under the influence of alcohol,” he said. VTDigger agreed to identify him by his first name so he could freely discuss his criminal history without facing further ostracization from his community.

Because of his previous felony convictions and parole status, Peter said he’d been terrified about the heavy penalties he might face in his latest DUI case. Soon after being detained in Rutland, he finally admitted to himself that he had a drinking problem he needed to fix.

A few days later, he saw a sign-up sheet for Turning Point’s prison programs and considered it a sign pointing to the way forward: recovery with the help of others. “By myself, I hadn’t had any success staying sober,” he said.

Besides receiving recovery coaching from Nielson, he attended two-month-long recovery courses — five times each. In one interview, Peter brought along a folder that contained his multiple certificates for completing those courses, “Smart Recovery” and “Making Recovery Easier.”

He also showed VTDigger his weekly schedule of activities while incarcerated, which included taking academic courses at Marble Valley, going to a church service and calling family members.

“That’s how I kept going, my motivation,” Peter said.

He was released on parole in July 2020 and is now renting a home in Rutland County. He is helping with the family business and has regained his driving privileges with the use of an ignition interlock, a breathalyzer connected to a vehicle ignition that prevents a vehicle from starting if the driver’s blood alcohol is above a certain level.

Peter said he doesn’t want to jeopardize this chance at being allowed to drive again. If he commits another driving violation, he said he’d likely be banned from driving for life.

He meets with Nielson once a week, speaks with the peer counselor by phone every day and attends several group meetings. Peter said he could very well have been behind bars again if it weren’t for the recovery center.

“They’re helping me save the rest of my life,” he said. “I can’t do it by myself.”

There’s a recovery center in all six Vermont municipalities with a correctional facility: Burlington, Newport, Rutland, Springfield, St. Albans City and St. Johnsbury. But aside from the one in Rutland, no other center is currently running a prison recovery program.

Gary De Carolis, director at the Recovery Partners of Vermont, a network of a dozen recovery organizations throughout the state, said other recovery centers have attempted establishing prison recovery programs — or re-establishing ones that had existed — but they have not succeeded for various reasons.

Two major factors need to line up for the outreach to materialize, he said: One, officials of a correctional facility open their doors to recovery center volunteers; two, a recovery center has extra resources to expand into a correctional facility.

“I think both things have to be just right,” De Carolis said. Unfortunately, he said, many recovery centers don’t have enough money to launch such an initiative.

Vermont’s corrections commissioner, Nicholas Deml, described Rutland Turning Point’s Marble Valley programming as a critical service for residents. He said it could be replicated in other correctional facilities, if their circumstances allow.

“The Department wholeheartedly supports employing similar substance use disorder recovery programs in other correctional facilities,” Deml told VTDigger in a statement. “That being said, each of our facilities has different capacities for volunteer programs based on geography, services in the community and availability of volunteers.”

(All of the state’s correctional facilities do provide medication-assisted treatment to incarcerated people who have opioid use disorders.)

The COVID-19 pandemic, Deml said, has contributed to both an increased need for social services, as well as a shortage of resources and volunteers to carry them out. As communities emerge from the pandemic and the corrections department continues to build its workforce, Deml said Vermont’s capacity to implement recovery programs and other support services will increase.

“Opportunely, the Turning Point program can serve as an important blueprint for the rest of the state as we imagine and develop these programs,” he said.

Research over the years has found that community support is critical to helping incarcerated people rebuild their lives when they return to society.

A 2012 study of formerly incarcerated individuals showed that community-based resources, including peer support groups such as Alcoholics Anonymous and Narcotics Anonymous, helped prevent relapses into drug or alcohol use.

The study said incarcerated people are often released without the tools necessary to help them avoid using substances again. Relapses can occur within weeks of being released, when people go back to places or companions associated with their old habits. Some fatally overdose because they misjudge their tolerance for drugs or alcohol after being locked up for some time.

Magdalena Cerda, director of the center for opioid epidemiology and policy at the NYU Langone Health system, believes there should be increased investment in recovery programs for incarcerated people, along with more evidence-based treatment for substance use disorder.

Cerda, whose research subjects include the effects that state and national drug and health policies have on substance abuse trends, said incarcerated people are especially vulnerable to reusing and overdosing once they’re released because they often don’t have readily available community support systems.

“Ensuring that there is actually a connection to care, and transitions in care, from correctional settings to community settings, I think it’s huge and vital,” she said in an interview.

To Nielson, the Turning Point recovery coach, prison recovery programs also show incarcerated individuals that they have a future in society. “They are not forgotten,” he explained. “Their whole world is not determined by being incarcerated.”

In February 2022, St. Pierre was released from Marble Valley to serve the remainder of his sentence in the community. He moved to a transitional home in Rutland for people recovering from substance use disorder, where he is responsible for maintaining the residence grounds.

Every week, he continues to see Nielson. Whenever his health permits, he attends group meetings at the Rutland Turning Point Center.

While incarcerated, St. Pierre said, he’d signed up for medication-assisted treatment to help alleviate his cravings for alcohol and drugs. Once he was out, he said, he weaned himself from the medication methadone because he no longer wanted to be dependent on any substance.

He had been sober for six years, then relapsed in mid-April. He drank two beers when he got so upset by a contentious relationship with a housemate. The next day, he made an admission to his parole officer, then his recovery coach at Turning Point.

“They just told me, ‘Honesty is the first part of never making that mistake again, and try to stay sober,’ ” he said.

Nielson commends all the hard work St. Pierre has put into his recovery, and says he has been on a very good trajectory. Nielson said relapses are not uncommon among people with substance use disorder, because their instinct is to retreat into themselves rather than reach out when they need help.

“The important thing is, he’s not trying to conceal it. He’s not running and hiding,” Nielson said. “He’s built up enough quality that it is recognizable that this is not some huge event. It’s a blip.”

Nielson said St. Pierre’s recovery journey is noteworthy in that, while incarcerated, he’d broken through the mental barriers that often afflict people who are behind bars. The recovery coach said St. Pierre maintained a positive outlook even while serving his sentence, advocated for his health care needs with the corrections department and established an honest relationship with his peer counselors.

“Once he got started, his mind left prison,” Nielson said. “It took hold in him, and he carried it with him.”

St. Pierre just bought a secondhand car with savings from his disability payments. He is working toward paying outstanding fines and passing a driving test, so he can finally get a driver’s license.

Although he started driving decades ago, St. Pierre has never gotten a driver’s license. He considers being able to obtain this pocket-sized ID an “accomplishment,” a hallmark of a normal life.

Zantop daughter: ‘I wish James' family the best and hope that they are able to heal’

Zantop daughter: ‘I wish James' family the best and hope that they are able to heal’ Chelsea Green to be sold to international publishing behemoth

Chelsea Green to be sold to international publishing behemoth